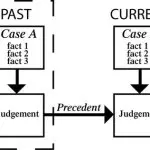

The doctrine of precedent is one of the principles that underpin common law. The Latin name for the doctrine of precedent is stare decisis (‘stand by that decided’). It is a principle that requires judges to follow the rulings and determinations of judges in higher courts, where a case involves similar facts and issues. The doctrine of precedent evolved in medieval England, at a time when law was being formed and judges wanted greater consistency and standardisation. Medieval judges were often appointed because of their social status, not their understanding of the law – so many were barely competent, hopelessly biased, or both. The development of common law and the doctrine of stare decisis required these judges to make more rational and consistent decisions. The common law system that emerged from Britain during the Middle Ages was stable, consistent and even-handed – at least when compared to other systems of the time.

The doctrine of precedent only applies when the court is actively considering a case. When a case comes before the court, in general terms the judge will follow this approach:

- Ascertain the facts by hearing from all parties, witnesses and reviewing evidence.

- Locate and review legislation that may be relevant and interpret the legislation, if necessary.

- Locate and review previous rulings, similar cases and precedents that may be relevant.

- Ascertain whether these precedents may apply to the case and its facts. If so, apply the precedent as previously defined.

- If no precedent applies to the case and its specifics – make a ruling that establishes a new precedent.

- Include in the judgement a ratio decendi, providing legal reasons for the judgement.

The court hierarchy is critical for the doctrine of precedent to function effectively. A precedent set in one court applies to all lower courts – but only in the same hierarchy. A precedent in the Supreme Court of Victoria, for example, is binding on the County Court of Victoria and the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria – however, it is not binding on courts in other jurisdictions, such as the Federal courts or courts of other States. A precedent can be overturned in a higher court in the same jurisdiction. A County Court precedent, for instance, can be appealed and overturned in the Supreme Court. This allows some flexibility, review and challenge of precedents; they are not set in stone.

R v. Downtown (1999)

In the hypothetical case of R v. Downtown (1999), Downtown is appearing before the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria. The specifics of the case are that Downtown’s house was on fire and that he did not own a hose. Fearing the spread of the fire, Downtown crossed into the yard next-door to use his neighbour’s hose. The neighbour, who was not home at the time, later insisted that Downtown be charged with trespass. These facts are not in dispute, however, Downtown has pleaded ‘not guilty’ on the basis that the law allows him to take reasonable steps to protect his property. Some scenarios include:

Scenario One. The legislation defines trespass as the unauthorised entrance onto property belonging to another party – on that basis alone Downtown has clearly committed trespass. Downtown’s lawyers have not highlighted any precedents from similar cases, so it is up to the judge to form his own ruling. He determines that the legislation should be applied strictly and finds Downtown guilty of trespass. However given the extenuating circumstances, he imposes only a small fine and does not record a conviction.

Scenario Two. The legislation defines trespass as the unauthorised entrance onto property belonging to another party – however, it also contains a clause stating that trespass “shall not have occurred if the party was seeking refuge or protection from assault, threat, attack or deprivation of property”. There are no relevant precedents to follow. The judge interprets this section of the statute broadly and rules in Downtown’s favour, stating in his ratio decendi that Downtown was “seeking… protection from… deprivation of property”. Downtown’s case is discharged.

Scenario Three. The legislation defines trespass as unauthorised entrance onto property belonging to another party – on that basis alone Downtown has clearly committed trespass. However Downtown’s lawyer points to a County Court judgement from 1892, from a case with similar circumstances; this judgement contains a ratio decendi stating that “the law of trespass should not apply to person(s) taking refuge from likely harm or seeking materials to protect their property from imminent destruction”. Because this precedent is from a higher court, the trial judge has no option but to acquit Downtown and discharge the case.

Scenario Four. The trial judge’s reading of the legislation finds that trespass is defined by intent – in other words, the reason(s) the accused entered the other party’s property. Under the act, trespass is defined as entering with intent to either spy, stalk, steal, assault, vandalise, destroy or gain financial advantage. There are no relevant precedents that the judge can use. The judge must form his own ruling, declaring the reasons for this in his ratio decendi. It may state, for example, that “the legislation offers no precise guidance on what constitutes trespass in circumstances where property is in danger…” and “…that trespass has not occurred in this case because the defendant had no intent as defined by the legislation”. Once entered, this precedent will be binding on lower courts.

© lawgovpol.com 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.