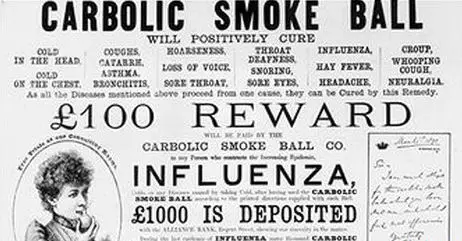

In the late 1800s, it was quite common for businesses selling medical and pharmaceutical products to make outlandish promises about their products. Because there were no real restrictions on advertising, product or trading standards, retailers often promoted their products as ‘miracle cures’. In the early 1890s one English firm, the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company, advertised a device it claimed would “positively cure” a range of ailments, including influenza. So confident was the company making this claim that it promised a reward of £100, payable to anyone who used its product in the correct fashion but later contracted influenza. The Carbolic Smoke Ball Company’s ad (see below) promised that £1,000 had been deposited at a London bank as a sign of the company’s good faith.

In the late 1800s, it was quite common for businesses selling medical and pharmaceutical products to make outlandish promises about their products. Because there were no real restrictions on advertising, product or trading standards, retailers often promoted their products as ‘miracle cures’. In the early 1890s one English firm, the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company, advertised a device it claimed would “positively cure” a range of ailments, including influenza. So confident was the company making this claim that it promised a reward of £100, payable to anyone who used its product in the correct fashion but later contracted influenza. The Carbolic Smoke Ball Company’s ad (see below) promised that £1,000 had been deposited at a London bank as a sign of the company’s good faith.

In late 1891, Mrs Louisa Carlill purchased one of the Carbolic Smoke Balls. Following the instructions closely, Mrs Carlill used it three times daily for a period of two months. At the end of this period, she subsequently contracted influenza. Represented by her husband, a qualified solicitor, Mrs Carlill attempted to claim the £100 reward but the company ignored three of his letters. As a consequence, Mrs Carlill initiated legal action against the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company. Her lawyers argued the company had breached the terms of the advertisement – and thus its contract with customers. The company’s lawyers, led by Herbert Asquith, a future prime minister of England, argued that the advertisement was “mere puff”. Its conditions were so vague, they argued, that it was not intended to be taken seriously.

The case progressed to the Court of Appeal. There had never been a case with a similar set of facts, so the three-judge bench had to develop a new precedent. After deliberation, they unanimously found in favour of Carlill. They concluded that a binding contract existed between the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company and Mrs Carlill, for several reasons. Firstly, though the reward was promoted unilaterally (“an offer to the world”) it was still legitimate. The only stated conditions were the customer’s correct use of the Smoke Ball, as per the instructions. Secondly, the advertisement induced customers to buy the Smoke Balls, involving an inconvenience to the customer and a financial advantage to the company. This transaction constituted an exchange of promises. Thirdly, the company’s claim that £1,000 had been deposited as surety suggested the offer of a reward – and therefore the contract between the company and its customers – was legitimate and binding.

The judgement set precedents in contract law that continue in both Britain and Australia. It established that an offer of contract can be unilateral: it does not have to be made to a specific party. Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball also established that acceptance of such an offer does not require notification; once a party purchases the item and meets the condition, the contract is active. It also established that such a purchase is an example of consideration and therefore legitimises the contract. Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Company (1893) was a landmark case in protecting the rights of consumers and defining the responsibilities of companies. It continues to be cited in contractual and consumer disputes today.

© lawgovpol.com 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.