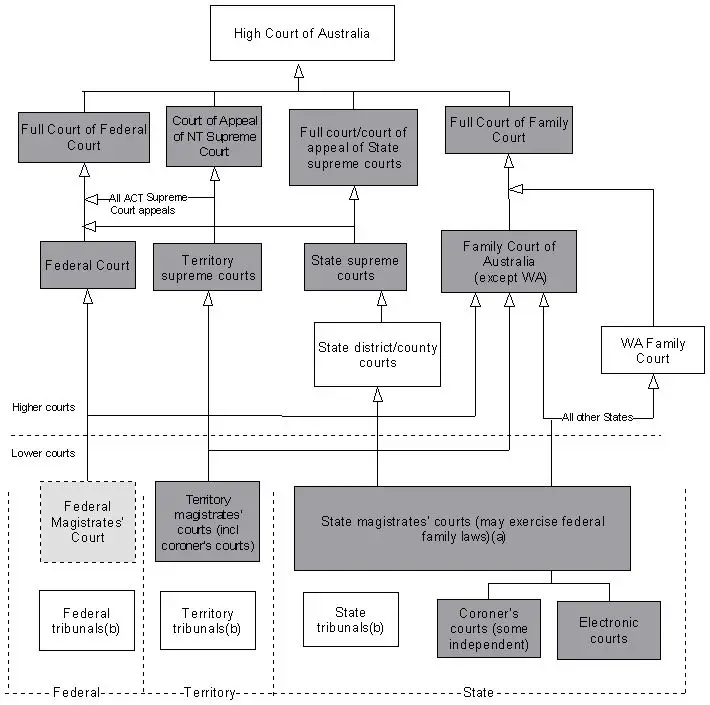

As in other countries, Australian courts are organised in hierarchies. A hierarchy is a structure where different levels or bodies are ranked or ordered, depending on their importance. In a court hierarchy, the different courts have different responsibilities. Lower courts, like the State Magistrates’ Courts, hear minor or less important cases – while the higher courts, like State Supreme Courts and the High Court of Australia, adjudicate more serious cases. Higher courts, which are also known as ‘superior courts’, can also hear appeals against decisions made in lower courts. In Australia, both Federal and State jurisdictions have their own court hierarchies. There is also some sharing and crossover between the two jurisdictions, in order to make better use of resources.

As in other countries, Australian courts are organised in hierarchies. A hierarchy is a structure where different levels or bodies are ranked or ordered, depending on their importance. In a court hierarchy, the different courts have different responsibilities. Lower courts, like the State Magistrates’ Courts, hear minor or less important cases – while the higher courts, like State Supreme Courts and the High Court of Australia, adjudicate more serious cases. Higher courts, which are also known as ‘superior courts’, can also hear appeals against decisions made in lower courts. In Australia, both Federal and State jurisdictions have their own court hierarchies. There is also some sharing and crossover between the two jurisdictions, in order to make better use of resources.

Federal court hierarchy

High Court. As its name suggests, this court is the highest in Australia. It can hear appeals from all other Australian courts, and its other chief function is to interpret the Constitution and determine whether legislation is constitutionally valid. The High Court is, in reality, part of both Federal and State court hierarchies.

Full Court of the Federal Court. This is the appeals division of the Federal Court (see below). Persons or parties unhappy with decisions made in the Federal Court may appeal to the Full Court, rather than seeking special leave to appeal to the High Court. The Full Court is comprised of a panel of three, four or five Federal Court Justices.

Federal Court. This court is the approximate equivalent of a State Supreme Court. Its original jurisdiction is to hear criminal and civil cases concerned with Commonwealth law. These cases may involve terrorism, immigration, customs, industrial relations, taxation and corporate law. Since crimes such as murder, attempted murder and assault are part of State criminal codes, the Federal Court does not hear these charges.

Family Court. Formed in 1975, the Family Court is a court of limited jurisdiction because it can only hear matters concerned with family law. Since the Commonwealth has legislative power over marriages, granted in Section 51(xxii) of the Constitution, the Family Court has jurisdiction over marital status disputes, annulments and divorces, as well as the residency and maintenance of children. In reality, the Federal Magistrates’ Court deals with most family law cases; only the more complex and drawn-out matters are referred to the Family Court.

Federal Magistrates’ Court. This is a relatively new court, formed in 1999. It was created to ease the caseload of the Federal Court, the Family Court and the State courts hearing Federal matters. Much of the Federal Magistrates’ Court’s workload is concerned with bankruptcy, administrative law, copyright disputes and family law. It also hears a large number of migration cases, such as appeals against visa and residency refusals. There are more than 60 Federal Magistrates currently in service.

State court hierarchy

High Court. Under the Constitution, the High Court can hear appeals from State and Territory Supreme Courts, as well as against the constitutionality of any State or Territorial legislation. This makes it the superior court in both Federal and State jurisdictions.

Court of Appeal. The Supreme Court in each State has an appeals division, variously called the ‘Court of Appeal’, the ‘Full Court’ or the ‘Court of Criminal Appeal’. These courts have appellate jurisdiction only: they are formed to hear appeals from the Supreme or County/District Court. In most cases, the Court of Appeal consists of three Judges of Appeal.

Supreme Court. These courts are the highest courts in each State and Territory. They hear the most serious of criminal offences, including murder, manslaughter and treason. Other charges involving multiple offences or great complexity may also be referred to Supreme Courts. They also hear civil disputes involving great complexity and large amounts of money.

County Court (Victoria) or District Court (NSW, South Australia, Queensland and Western Australia). This is an intermediate court, hearing criminal trials for serious indictable offences. It has jurisdiction to hear all but the most serious of criminal charges, such as murder and manslaughter.

Magistrates’ Court. The lowest or ‘inferior’ court of record, the Magistrates’ Court deals with minor criminal offences, most of which can be tried without the need for a jury. Magistrates’ Courts also hear civil disputes up to the value of $100,000. They also conduct committal hearings to decide if there is sufficient evidence for serious criminal charges to be heard in the Supreme Court. In New South Wales, this level of court is called the Local Court. On Norfolk Island, a self-governing Australian territory, it is called the Court of Petty Sessions.

Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory all have two-court hierarchies: they do not have an intermediate court, only Magistrates’ and Supreme Courts. Western Australia has all three court levels plus a State-based Family Court – the only State to do so. This diagram shows the organisation of Federal and State courts in greater detail:

© lawgovpol.com 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.